Forty thousand people have passed through Bosnia since 2018, and up to six thousand are stuck in the Una-Sana canton, where Bihać is, while they wait to try to cross the border into Croatia, Europe’s first outpost. Migrants call their attempts to cross into Europe and evade Croatian border patrol “the game” – a game they have to restart multiple times, paying a high price in suffering, money and time. At the border, in the woods, chances are high that the refugees will encounter the violence and batons of the Croatian police and be returned to Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has become a sort of buffer state on the margins of Europe.

Even if the refugees arriving in Bosnia and Herzegovina do not intend to stay, the closure of European borders has produced a humanitarian crisis in the Balkans, which feeds racism and xenophobia. In cafes lining Bihać’s main street, there is an unwritten rule: refugees cannot sit at the outside tables:

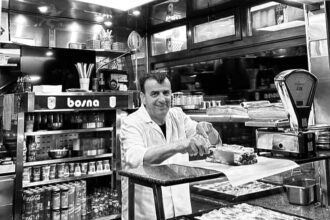

“The owners of all the bars have decided not to allow migrants to sit, even if they pay. The problem is that they don’t wash, they stink,” says Nerning, a bar owner. “Our customers are afraid of the diseases migrants carry”.

Initial empathy

Despite no incidents to speak of, the citizens of Bihać seem exasperated by refugee arrivals. It wasn’t always this way. During the Balkan Wars, more than a million people fled Bosnia, some returning after the conflict. According to Abdurahman Osmanović, Bihać’s imam, locals initially demonstrated empathy towards today’s migrants. “They know what it means to leave their homes behind,” he says.

Yet for some time now, that empathy seems to have cracked. While scooping ice cream into cones for her customers, Azerina Junuzović, a woman in her sixties and owner of RB Bar, on the main street, is keen to point out that today’s Afghan, Syrian and Iraqi refugees are not in the same situation that Bosnians faced in the nineties:

“It’s another type of migration. They escape from their country more for economic reasons than for war”.

Memory seems erased, empathy dissolved.

To avoid alienating the population in view of the 2020 elections, Bihać mayor Šuhret Fazlić decided first to deport the refugees to Vučjak, and then to dismantle the camp, which housed up to 1,500 at any one time. At an October 21 press conference in Sarajevo, Fazlić announced that the local administration would no longer pay the camp’s expenses, cutting the water supply, electricity and waste collection.

Winter weather then turned the situation into a major humanitarian crisis. On December 3 the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights Dunja Mijatovic said Vučjak should be shut down immediately. “If we don’t close the camp today, tomorrow people will start dying here”, she told reporters while visiting the camp. “Whose responsibility would that be? That is the question I ask everyone.” Mijatovic, a Bosnian national, said she was upset by the situation. “I think this is a shame for Bosnia. The conditions here are not for human beings”.

During the migrant and refugee crisis in 2015 – 2016, IOM – the UN Migration Agency – together with the international community, scaled up its presence in Greece and the Western Balkans, and in particular in North Macedonia and Serbia part of the so-called Western Balkan route, to support national authorities and civil society in responding to the emergency situation, and providing direct assistance and protection to migrants, particularly those most vulnerable to violence, exploitation and abuse, or a violation of their rights.

Following the significant increase of migrant arrivals to Bosnia and Herzegovina in late 2017, IOM, in coordination with State, Entity, cantonal and local authorities, scaled up its operations in key migrant locations across the country through the reinforcement of IOM Mobile Protection Teams. These mobile teams have been operating since June 2017, assisting migrants in vulnerable situations, providing safe transportation, interpretation services, provision of temporary and protection-sensitive accommodation, food and other necessities.